Sue Whigham explores the origins of many popular plant species and how they were discovered

I must say that when my son and daughter-in-law announced that they were going to take a sabbatical in the summer of 2019 and, with their daughters aged six and four, travel to Colombia, I initially had alarming visions of dangerous jungle trails, groups of heavily armed FARC rebels and threat of kidnap.

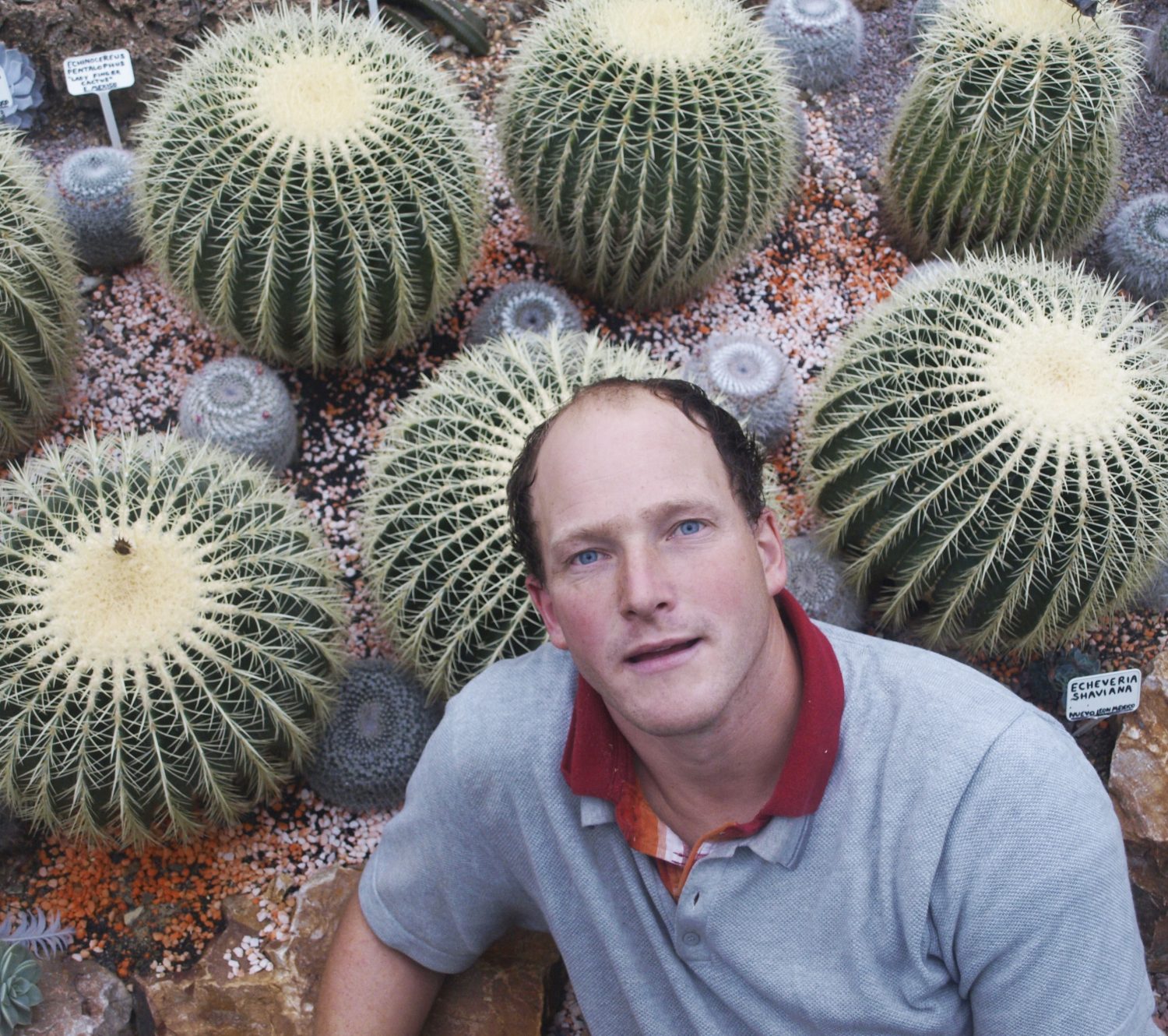

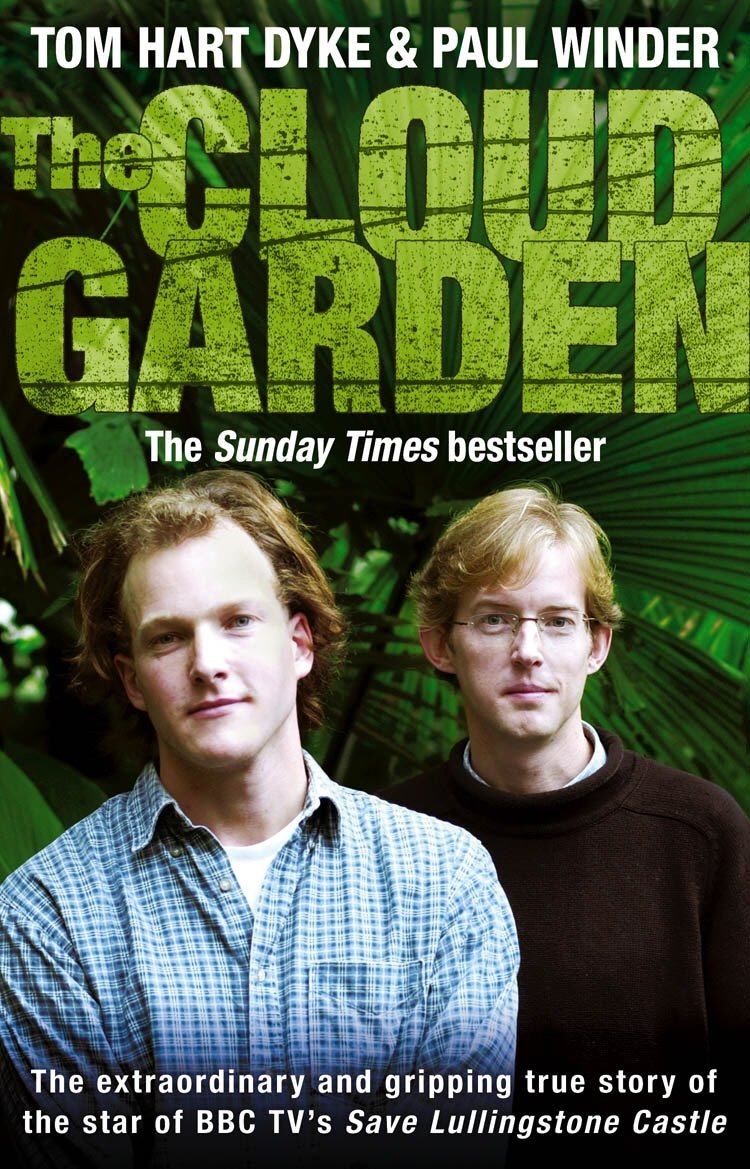

I suppose what I was thinking of is what happened to Tom Hart Dyke from Lullingstone Castle and his travelling companion, Paul Winder, back in 2000. They found themselves in the inhospitable jungle of the Darién Gap between Panama and Colombia with Tom following his wild enthusiasm for orchids and Paul in his pursuit of adventure. They were kidnapped by a rebel group and spent nine months in their company. Since then, Tom, a modern day plant hunter, has undertaken many other plant hunting trips, including one to Central Peru in 2009 where he came upon an entire clump of Puya raimondii (Queen of the Andes) flourishing at over 14,000 feet where virtually nothing else grows. This particular bromeliad is on the endangered list in the wild. To see the plant flower must be extraordinary. Some of the flower spikes are over 44ft tall with each producing over 10,000 creamy white flowers. And to cap it all, the flowers are pollinated by hummingbirds. Can you just imagine it?

And then, in a chance conversation at a recent meeting of the local Hardy Plant Society, I got talking to a friend who said she was related, she knew not how, to Reginald Farrer who made his name with his book, My Rock-Garden, in 1907. This book kindled a huge interest in alpine plants and rockeries amongst British horticulturalists of the time. She also grows and loves alpine plants so it must be in the genes.

Reginald was born in 1880 in Clapham, North Yorkshire, and was heir to the estate of Ingleborough Hall where some of his plant introductions are still to be found. He was seen as an eccentric and somewhat difficult man but his scope of exploration and search for, in particular, alpine plants which started in the European Alps led to expeditions further east taking in, amongst others, countries such as Japan and Korea, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as well as two forays into China. I spotted one of his introductions from China, Viburnum farreri (fragrans) in full fragrant flower at the weekend.

I like the story of him wanting to replicate a plant covered rock face that he’d spotted in Ceylon. He rowed out onto a lake near his home, loaded his shotgun with seeds collected on one of his expeditions and fired it into the nearest rock face. Many of them took and this piece of Yorkshire became the only true natural rock garden in the country at the time.

According to some records, active plant hunting dates from 1495 BC when Egyptian pharaoh, Queen Hatshepsut, commissioned an expedition to go to Somalia in search of incense trees, Commiphora myrrha, the tree from which the resin, myrrh, is derived. And subsequently the Romans, as they expanded their Empire, whilst not actively plant hunting, introduced non-native plants to our shores as foodstuffs. Think of the ubiquitous ground elder and the rather glamorous umbellifers, ‘Alexanders’ that grow along the coast in Kent and Sussex.

“The RHS, founded in 1804 ‘for the improvement of horticulture’, sponsored a number of important collectors who braved incredible hardship to feed the ongoing demand for anything new and exotic”

After that, medieval monks would have exchanged medicinal plants through their monasteries both here and in Europe. Up until the mid sixteenth century, most new plants would have come from Europe until the Middle East became a source of horticultural treasure as the plant hunters of the time spread their nets further afield.

And in the 17th century came two hugely influential generations of the Tradescant family. John Tradescant the elder, (1570-1638) was gardener to Charles I and his son, John the younger (1608-1662), was gardener to Charles II’s wife, Catherine of Braganza. They both travelled extensively in North America returning with hitherto unknown plants, amongst them the tulip tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, the swamp cypress, Taxodium distichum, plane trees and pineapples. They are both buried in the churchyard of St Mary at Lambeth, which stands close to the gatehouse of Lambeth Palace. The church was de-consecrated in the 1970s and in 1977 became the Museum of Garden History.

If you have a chance to go to Lambeth Palace Gardens, and it is open to the public on certain days, you can see a particularly fine specimen of Liliodendron tulipifera there – look out for the pineapples on the columns of nearby Lambeth Bridge which commemorate the Tradescant’s introduction of such an exotic fruit.

Subsequently, The Royal Horticultural Society, founded in 1804 ‘for the improvement of horticulture’, sponsored a number of important collectors who braved incredible hardship in far flung countries of the world to feed the ongoing demand for anything new and exotic. They included famous names such as Robert Fortune, George Forrest, David Douglas and Frank Kingdon-Ward, all of whose exploits are, quite frankly, hair-raising. Both the RHS and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew continue now to work with people on plant and seed collecting forays, including Tom Hart Dyke.

Sue and Bleddyn Wynn-Jones of Crug Farm Plants in North Wales were originally farmers but combined their love of plants and travelling more than 20 years ago to travel the globe seeking out specimens that grow in an equitable climate and which will therefore survive our weather conditions. They travel together or sometimes with friends and fellow botanists. Their usual modus operandi is to leave their nursery in the autumn for two or three months, having chosen a country and read up on the flora growing there and those plants they think might be hardy enough for our climate in England.

They make contact with local universities and work with local botanists sharing information and knowledge. They also follow strict quarantine rules, a must these days to guarantee biosecurity. Usually Bleddyn sends any seeds he has collected by runner to Sue at ‘base camp’ where she sets to cleaning, drying and packaging them up. The whole procedure is a lengthy one as often the quantity of seed is small and germination can, in some cases, take years.

The walled garden at their nursery is full of exotic looking plants and unfamiliar genera. Their Chelsea garden in the Royal Pavilion last year showed an interesting selection of plants for dry shade and included plants such as unusual aspidistera – just what we need with ever increasing parched summers in the South East – from Vietnam and South China as far as I can remember. The oreopanax they grow is very exotic and rather fabulous. As is the hardy Schefflera taiwaniana with huge and jungly leaves. They have an interesting website, to say the least.

So plant hunting continues with entrepreneurial private nurseries collecting plants and seeds from countries which weren’t always open for exploration. And like the plant hunters of old, they are highly motivated as they were and perhaps a little bit obsessed. They have found hardier forms; have discovered plants with ‘garden potential’ and plants which will form the basis of hybridising more and more interesting and beautiful varieties.

I remember visiting ‘backstage’ in the wondrous Kirstenbosch Garden in Cape Town really quite a few years ago and then they had people scouring other parts of South Africa for plants that might prove to be garden worthy in Europe. It all took time and each plant would be grown on and observed long before they were launched on to the horticultural public.

Imagine how dull our gardens might have been but for the plant hunters and how lucky we are to have a climate that can accommodate such a huge range of plants. There is even a Puya raimondii growing at the World Garden at Lullingstone. I wonder if Tom Hart Dyke grew it from seed. I know that the plant, being monocarpic, needs to and does produce literally thousands of seeds before dying.

lullingstonecastle.co.uk

crug-farm.co.uk

Sue Whigham can be contacted on 07810 457948 for gardening advice and help in the sourcing and supply of interesting garden plants.

TEST

In 1495 BC Egyptian pharaoh, Queen Hatshepsut, commissioned an expedition to Somalia in search of incense trees, Commiphora myrrha

TEST

In 2000, modern-day plant hunter Tom Hart Dyke was captured, along with his friend Paul Winder, by a rebel group in The Darién Gap while on an expedition to discover orchids. They wrote about their ordeal in their best-selling book, The Cloud Garden

TEST

In 2000, modern-day plant hunter Tom Hart Dyke was captured, along with his friend Paul Winder, by a rebel group in The Darién Gap while on an expedition to discover orchids. They wrote about their ordeal in their best-selling book, The Cloud Garden

TEST

Queen of the Andes, Puya raimondii, flourishing in its natural habitat. The flower spikes can reach as much as 44ft tall

You may also like

Go with the Flow

Sue Whigham shares some valuable new-to-gardening advice I’m sure that by now we should be used to the rain but I’m not entirely sure that we are. We had a dry, sunny day the other day and how everybody’s mood...

Farm Fables

Jane Howard gets to the bottom of why so many ponds have disappeared across the High Weald I have a new passion, almost an obsession, it’s about ponds. And there’s a distinct possibility I might become a bit of a...

Hedge Issues

Sue Whigham takes a meander along nature’s verdant and vital corridors Recently the BBC’s Today programme carried a feature about England’s hedgerows which created a lot of interest among listeners. On the strength of that, Martha Kearney interviewed one of...