On a bright desert day in June, 1918, a young Icarus fell from the timeless skies of Egypt and in those few short moments of his fall was transformed from a joyful and charismatic son, brother, friend and comrade into a statistic – one of more than a million British and Commonwealth soldiers, sailors and airmen who lost their lives and dreams in The Great War.

At the close of this terrible conflict, a grateful and grieving nation vowed that ‘at the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.’ This was the war to end all wars and could lives be lost in a nobler cause? Alas, in this respect, The Great War failed, and within 21 short years, Europe found itself involved in an even more appalling nightmare. When peace finally came there were new deaths to mourn, a world to be rebuilt. The memories of the horrors and sacrifices of 1914-18 began to fade. The years past and The Great War became relegated to the ‘unnecessary’ war.

The centenary, thankfully, has changed all that. A re-examination has taken place of both the causes of the war and its conduct. Wiser minds have concluded that it was an unavoidable war and that although mistakes were made aplenty, both generals and politicians were moving in dark, uncharted waters.

To our young airman the doings of neither were of great interest. He had joined up in November – from duty certainly but also to be part of a great adventure that might only last a few weeks. For him, those few weeks turned into months and then years during which time he rose through the ranks of the infantry to be commissioned as a pilot in the newly-formed RAF.

The pilot was my uncle, my father’s eldest brother, and his death devastated my father’s family. What he had been doing in those four years before his death were to me though, a mystery. Talking about him was almost impossible for the family. The mere mention of his name, even 70 years later, would immediately bring tears to my aunts’ eyes and send my father off on a solitary dog walk.

Finally, I did my own research and found and visited his grave in Alexandria. As more documents started to appear online, I began to piece together the story. After basic training he had been thrown into the hell of Gallipoli, survived, was posted first to Egypt and then to Palestine where he fought in the First, Second and Third battles of Gaza and the battle of Jaffa and, again, survived. I learned a great deal about the man as well as the soldier. He was a talented musician, first-rate sportsman, had a V.A.D sweetheart in Cairo and would always light up a Passing Cloud immediately on stepping out of his aircraft.

So today, he is no longer a statistic. An airfield photograph of him in full flying leathers, Passing Cloud between his lips, stands on our sideboard. He has now returned, if in spirit only, to his family. My sons know him, his story and his war. To them, WW1 has meaning beyond dry history lessons and a few old newsreels. To them it is a time when ordinary men and women did extraordinary things and many never returned to tell their tale.

However, they could never have reached this appreciation by remaining in the classroom or even on a conventional school tour of the battlefields. Children do not register tragedy in terms of millions of dead. To them, vast immaculate cemeteries are just vast immaculate cemeteries and vast empty fields. Children do not think in numbers. They think in people.

So if you would like to give your child an appreciation of this exceptional time in our history, one way is to help them find a guide, someone to take them back and walk beside them through those extraordinary years. Step back a couple of generations and most families have an ancestor who died in the Great War. If your family doesn’t, your town or village will. Alas, there are enough names to choose from on any war memorial. Find a name and you have found your guide.

The aim is to find out as much about your guide as possible – his regiment, when he served, where he fought, how he died, where he is buried or on what memorial overseas he is honoured. But as important, is to try to find out who he really was. He wasn’t always a soldier, so who was he? Where did he live? Who were the parents to whom he wrote? Who were the brothers and sisters he missed? Was he married? Did he have children of his own?

A surprising amount of this information is now online in one form or another and it is amazing how quickly a life can come together. Ideally, the final step will be to find his grave if it’s known – easily enough accomplished by a visit to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website – and to make a visit combined with a tour of the local battlefields were he fought.

Some battlefields tell their story more willingly than others. The Belgian battlefields tend to be more reticent than those of the Somme. Villages and towns have been rebuilt and have grown and so it is more difficult to imagine the landscape of the time. The Somme is virtually, copse for copse, exactly as it was in 1916. You can lay an old trench map over a Google map and the difference might be the odd tree or tractor.

The Somme cemeteries, too, are smaller, more intimate and tend to be associated closely with specific actions. In short, more comprehensible and emotionally accessible to a child. And finally there is Lutyens’ Thiepval Memorial – that commemorates more than 72,000 UK and South African officers and men who have no known grave – and, nearby, the excellent Thiepval Visitor Centre.

The Centre is great for children and young adults. It gives them a break from plodding round fields and being talked at and allows them to do a little discovering on their own. Particularly poignant and valuable is the panel that greets visitors as they walk in – a montage of 600 pictures of soldiers whose names are on the memorial. There is also a small cinema showing three 10-minute films which tell the story of the Somme and a bank of PCs linked both to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website and the Centre’s own Database Project.

The latter is particularly interesting in that it aims to collect as much information possible – including pictures – on each of the missing named on the memorial and could be extremely valuable to anyone researching one of these men. The Database isn’t available online and can only be accessed through the Centre’s own PCs.

But whether your child’s guide fought on the Somme or Ypres, Cambrai or the furthest reaches of the Empire is irrelevant. His task will be to lead your child through his extraordinary life and give them an insight into one of our country’s most testing times. In return, your child will be ensuring that their soldier is no longer just a statistic, no longer just a fading name on a village memorial.

When I visited my uncle’s grave I noticed that, below his name, age and the date of his death were just two words, Safe Home. By keeping his memory alive, my family have ensured that he indeed returned and, I hope, will always be safely with us.

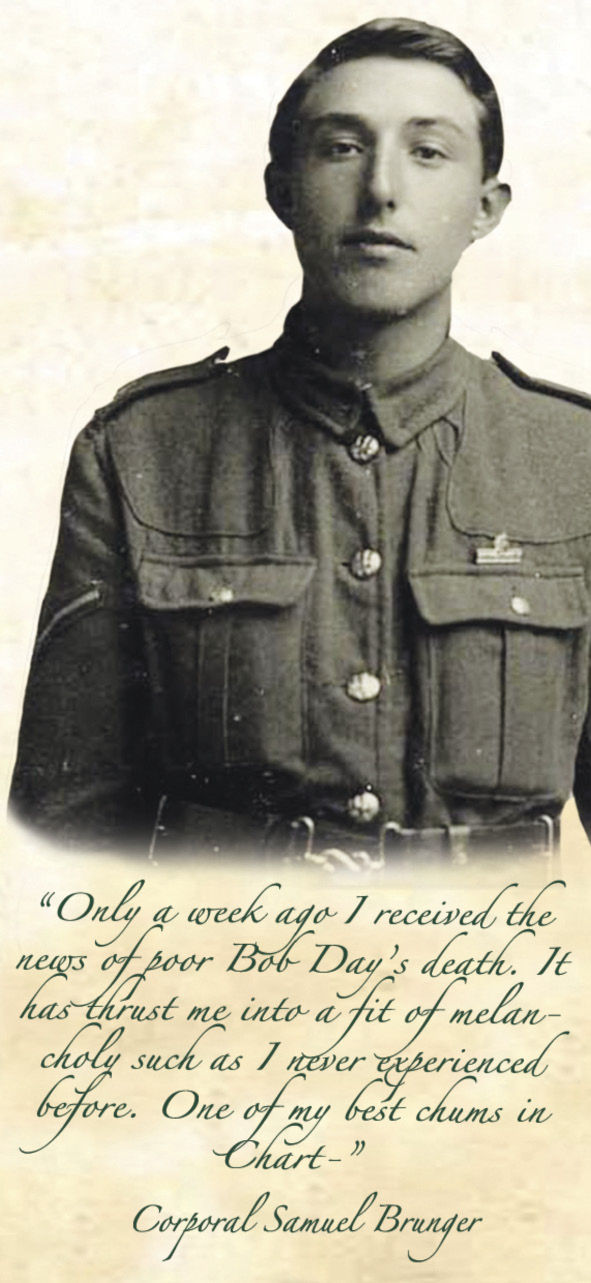

An extract from the final letter of Corporal Samuel Brunger, who died in fighting near Jerusalem, is being shown as part of ‘Letters from the Front’ at Godinton House near Ashford. The exhibition, which features ther personal stories of the men of Great Chart and Godinton who served during WW1, will run until 31 October. For info visit www.godintonhouse.co.uk

TEST

2nd Lieutenant F. W. Graham-Hart

TEST

Soldiers of the Lancashire Fusiliers, 29th Division, are seen on board an old Royal Navy battleship used in the third phase of operations in the Dardanelles Straits before they disembarked at ‘W’ and ‘V’ beaches off Cape Helles on 5 May 1915

TEST

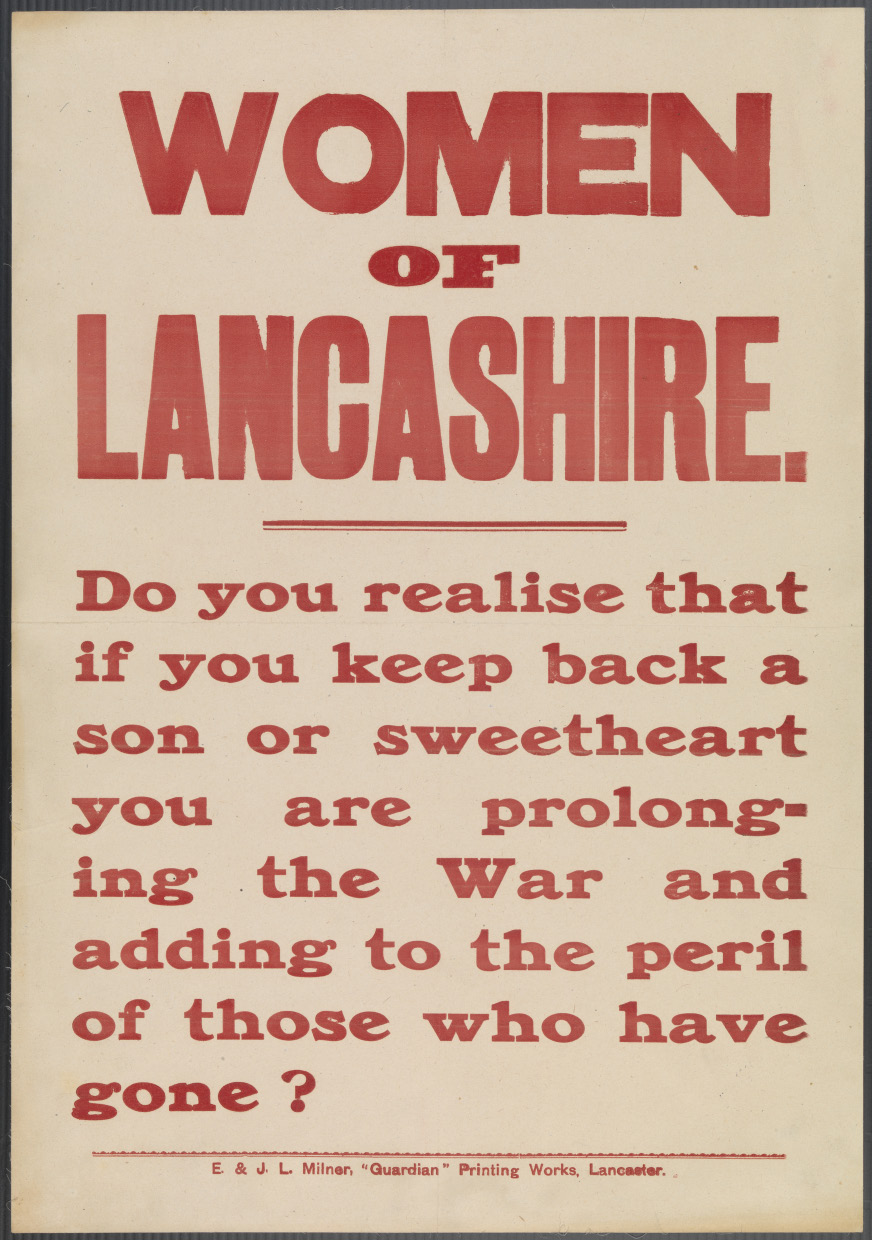

Recruitment poster appealing to women of Lancashire to encourage their male loved ones to join the armed forces.

TEST

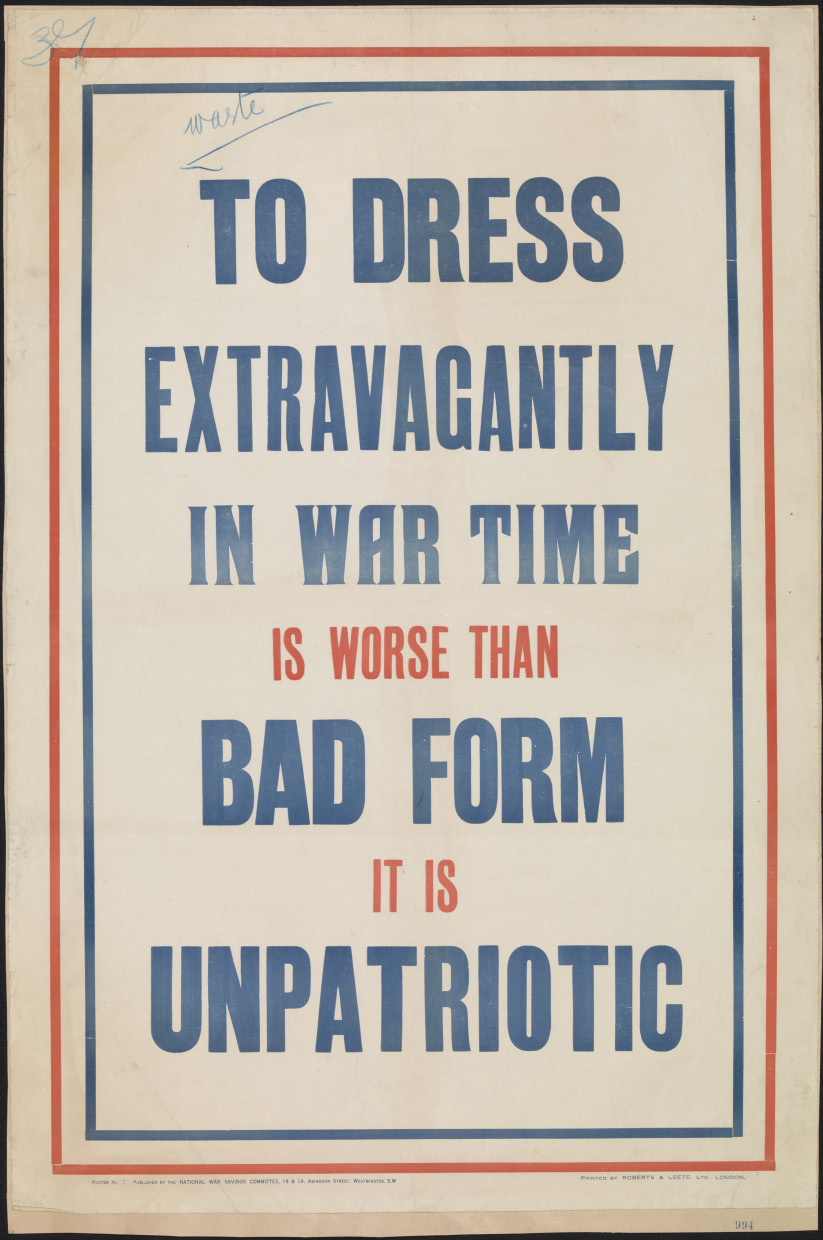

Poster from 1916, a time when Britain’s war effort became much more tightly organised. People were increasingly encouraged to use fewer resources and work harder and longer, all for the sake of winning the war. (All images courtesy of The Imperial War Museum)

TEST

An extract from the final letter of Corporal Samuel Brunger, who died in fighting near Jerusalem, is being shown as part of ‘Letters from the Front’ at Godinton House near Ashford

TEST TEST

TEST

You may also like

Perfect Pitch

Mike Piercy, education consultant and former Head of The New Beacon, sings the praises of music in education What exactly is it that drives parents to make huge sacrifices by sending their children to independent schools? Different families have different...

‘It’s not fair!’

Mike Piercy, education consultant and former Head of The New Beacon, explains the importance of winning and losing with good grace The beefy second row lay prone, groaning, as the pack lumbered away. “Get up, Darling!” I cried. Opposition spectators...

Performance Power

Eastbourne College and Bede’s School discuss opportunities which give their students time to shine Director of Music at Eastbourne College, Dan Jordan, sings the praises of music at the school. It is 6.30pm, the night before a well-needed half-term holiday....